Ahab was a monster.

I was afraid of him the instant I started this project. Even more so than with the white whale itself, I knew that whatever choices I made in depicting Ahab would loom large over the entire series. I was quite literally terrified, and I lived in dread of illustrating him. I knew the day would come, but the less I had to think about it the better. The pressure was staggering.

Perhaps that was because I knew Ahab came with expectations. Many are familiar with Gregory Peck’s turn playing the role. Less, perhaps, know Rockwell Kent’s Ahab specifically, but enough have seen it in various editions that I knew I had to battle against that as well. Beyond those two examples, books and movies and comics and paintings and prints and all sorts of other ephemera, whether they cluttered the pop culture landscape or filled the drawers of museums and archives, bore Ahab’s image and like a kaleidoscope filled the world of the novel with a fragmented panorama of monomaniacs.

As always, I began with the details. Delightfully, Melville doesn’t skim with these regarding his lunatic captain. After pages and pages of whispered rumors and half-myths, Ahab finally appears in the flesh in chapter 28, after this incredible line of text…

Reality outran apprehension; Captain Ahab stood upon his quarter-deck.

That possessive touch, “his quarter-deck,” is a brilliant touch foreshadowing just how much control Ahab now has over his sailors’ lives. And deaths.

Melville continues…

There seemed no sign of common bodily illness about him, nor of the recovery from any. He looked like a man cut away from the stake, when the fire has overrunningly wasted all the limbs without consuming them, or taking away one particle from their compacted aged robustness. His whole high, broad form, seemed made of solid bronze, and shaped in an unalterable mould, like Cellini’s cast Perseus. Threading its way out from among his grey hairs, and continuing right down one side of his tawny scorched face and neck, till it disappeared in his clothing, you saw a slender rod-like mark, lividly whitish. It resembled that perpendicular seam sometimes made in the straight, lofty trunk of a great tree, when the upper lightning tearingly darts down it, and without wrenching a single twig, peels and grooves out the bark from top to bottom, ere running off into the soil, leaving the tree still greenly alive, but branded. Whether that mark was born with him, or whether it was the scar left by some desperate wound, no one could certainly say.

There was enough, indeed more than enough, in that one passage for me to begin. And in spite of my terror, I did have my own ideas. There was some madness there, yes, but above all, there is a great unknown quality about Ahab. He appears strong, robust, “made of solid bronze” and yet he looks “like a man cut away from the stake, when the fire has overrunningly wasted all the limbs without consuming them.” A paradox. Ahab is both brutally vibrant yet curiously and almost invisibly wasted and desiccated.

Continuing to explore my own visual vocabulary of imagining these whalemen as ship like constructs themselves, I saw Ahab as some kind of an avatar. The ideal, perfect whaleman. Even here, nearing his own unknown and unexpected death, consumed by hatred and vengeance, he was shrouded in power and glory. His image had to reflect that might and the drawing itself had to show fealty to the man. I knew I would need to spend much much more time than usual, but I felt immediately that an ornate border needed to decorate the drawing, creating the feeling of an icon. In a bit of visual foreshadowing, I decorated the corners of the border with a blood-red quarter circle enclosing the shape of a fleeing white whale-tail presaging Ahab’s deadly pursuit of the unreachable and unconquerable Moby Dick. Also, in keeping with the grotesquely baroque designs of his ship the Pequod, Ahab was decked out like a barbarian king with a great belt, a massive spiked belt buckle depicting (again) the white whale, and a great coat swirling with the colors of the sea. A thick and brutal harpoon jutted from his right shoulder, seemingly encased in his body and ready to be fired forth as if from the cannon of his chest. Finally, Ahab’s great head sat on his body like a turret. I felt that I absolutely had to push the curious and slightly disturbing image of that “lividly whitish” scar to the fore as an outward, obvious symbol of Ahab’s inner maiming…

This first image of Ahab was grand, as suits the man. All perfect lines and curves delicately shaded and lavished with care. But I knew Ahab himself would undergo a drastic transition throughout the novel and once I had settled on how to depict him, I relished the thought of showing his deepening madness and steady unraveling. This I would show in the choice of media and the fury of the brushstrokes delineating him. First, and almost immediately after appearing on “his quarter-deck,” Ahab savagely rebukes Stubb, advancing on him with “overbearing terrors in his aspect.”

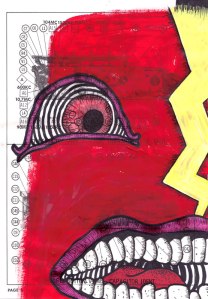

Next, one of the most definitive lines from the novel, Ahab’s cry of “I am madness maddened.” I began to experiment with subtle and not-so-subtle changes in Ahab. His head, somehow, in my mind had become a great scale-armored helmet. The eye, once so perfectly and geometrically rendered now grew and bulged and leered. The head was now riven from above, not by a simple scar but by a great bolt of divine lightning. His unmoored, maddened head seemed to float, sprouting wires and circuits and pipes rather than veins and sinews and blood.

Here, Ahab in an almost reflective moment, scrutinizing his charts and maps, obsessed with the hunt for Moby Dick while the lone lamp in his cabin swings and sways over his head.

Finally, what has come to be not only my favorite image of Ahab, but my favorite of the series of illustrations this far. Ahab, at the gam with the Goney (or Albatross) looking over the side of the ship at schools of small fish which had suddenly darted away from the Pequod and arranged themselves near the Goney. The line illustrated here is “’Swim away from me, do ye?’ murmured Ahab, gazing over into the water. There seemed but little in the words, but the tone conveyed more of deep helpless sadness than the insane old man had ever before evinced.” This is perhaps the only instance in the novel where Ahab’s madness and hateful thirst for vengeance gives way and reveals the agony and pain he labors under. Ahab is heartsick, dying inside, forever removed from joy and numb to any feelings of warmth and kindness. Some part of Ahab truly is aware of his own sickness, of the death inside of him, and at this moment, with this one line and this longing look at the fish fleeing from him, Ahab shows that “deep helpless sadness.”

Not that what an artist avows can ever be

the last we had seen of this version of the series,

but reconsidered after they successfully aired in Britain and America cartoon through three centuries.